Statistical hypothesis testing

A statistical hypothesis test is a method of making decisions using data, whether from a controlled experiment or an observational study (not controlled). In statistics, a result is called statistically significant if it is unlikely to have occurred by chance alone, according to a pre-determined threshold probability, the significance level. The phrase "test of significance" was coined by Ronald Fisher: "Critical tests of this kind may be called tests of significance, and when such tests are available we may discover whether a second sample is or is not significantly different from the first."[1]

Hypothesis testing is sometimes called confirmatory data analysis, in contrast to exploratory data analysis. In frequency probability, these decisions are almost always made using null-hypothesis tests (i.e., tests that answer the question Assuming that the null hypothesis is true, what is the probability of observing a value for the test statistic that is at least as extreme as the value that was actually observed?)[2] One use of hypothesis testing is deciding whether experimental results contain enough information to cast doubt on conventional wisdom.

A result that was found to be statistically significant is also called a positive result; conversely, a result that is not unlikely under the null hypothesis is called a negative result or a null result.

Statistical hypothesis testing is a key technique of frequentist statistical inference. The Bayesian approach to hypothesis testing is to base rejection of the hypothesis on the posterior probability.[3] Other approaches to reaching a decision based on data are available via decision theory and optimal decisions.

The critical region of a hypothesis test is the set of all outcomes which cause the null hypothesis to be rejected in favor of the alternative hypothesis. The critical region is usually denoted by the letter C.

Contents |

Examples

The following examples should solidify these ideas.

Example 1 – Courtroom trial

A statistical test procedure is comparable to a criminal trial; a defendant is considered not guilty as long as his or her guilt is not proven. The prosecutor tries to prove the guilt of the defendant. Only when there is enough charging evidence the defendant is convicted.

In the start of the procedure, there are two hypotheses  : "the defendant is not guilty", and

: "the defendant is not guilty", and  : "the defendant is guilty". The first one is called null hypothesis, and is for the time being accepted. The second one is called alternative (hypothesis). It is the hypothesis one tries to prove.

: "the defendant is guilty". The first one is called null hypothesis, and is for the time being accepted. The second one is called alternative (hypothesis). It is the hypothesis one tries to prove.

The hypothesis of innocence is only rejected when an error is very unlikely, because one doesn't want to convict an innocent defendant. Such an error is called error of the first kind (i.e. the conviction of an innocent person), and the occurrence of this error is controlled to be rare. As a consequence of this asymmetric behaviour, the error of the second kind (acquitting a person who committed the crime), is often rather large.

| Null Hypothesis (H0) is true He or she truly is not guilty |

Alternative Hypothesis (H1) is true He or she truly is guilty |

|

|---|---|---|

| Accept Null Hypothesis Acquittal |

Right decision | Wrong decision Type II Error |

| Reject Null Hypothesis Conviction |

Wrong decision Type I Error |

Right decision |

A criminal trial can be regarded as either or both of two decision processes: guilty vs not guilty or evidence vs a threshold ("beyond a reasonable doubt"). In one view, the defendant is judged; in the other view the performance of the prosecution (which bears the burden of proof) is judged. A hypothesis test can be regarded as either a judgment of a hypothesis or as a judgment of evidence.

Example 2 – Clairvoyant card game

A person (the subject) is tested for clairvoyance. He is shown the reverse of a randomly chosen playing card 25 times and asked which of the four suits it belongs to. The number of hits, or correct answers, is called X.

As we try to find evidence of his clairvoyance, for the time being the null hypothesis is that the person is not clairvoyant. The alternative is, of course: the person is (more or less) clairvoyant.

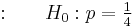

If the null hypothesis is valid, the only thing the test person can do is guess. For every card, the probability (relative frequency) of any single suit appearing is 1/4. If the alternative is valid, the test subject will predict the suit correctly with probability greater than 1/4. We will call the probability of guessing correctly p. The hypotheses, then, are:

- null hypothesis

(just guessing)

(just guessing)

and

- alternative hypothesis

(true clairvoyant).

(true clairvoyant).

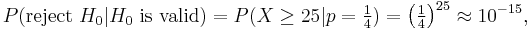

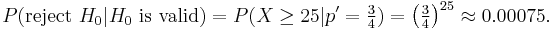

When the test subject correctly predicts all 25 cards, we will consider him clairvoyant, and reject the null hypothesis. Thus also with 24 or 23 hits. With only 5 or 6 hits, on the other hand, there is no cause to consider him so. But what about 12 hits, or 17 hits? What is the critical number, c, of hits, at which point we consider the subject to be clairvoyant? How do we determine the critical value c? It is obvious that with the choice c=25 (i.e. we only accept clairvoyance when all cards are predicted correctly) we're more critical than with c=10. In the first case almost no test subjects will be recognized to be clairvoyant, in the second case, a certain number will pass the test. In practice, one decides how critical one will be. That is, one decides how often one accepts an error of the first kind – a false positive, or Type I error. With c = 25 the probability of such an error is:

and hence, very small. The probability of a false positive is the probability of randomly guessing correctly all 25 times.

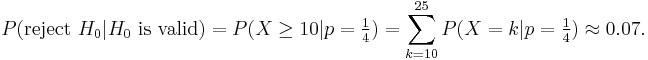

Being less critical, with c=10, gives:

Thus, c = 10 yields a much greater probability of false positive.

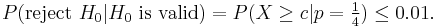

Before the test is actually performed, the desired probability of a Type I error is determined. Typically, values in the range of 1% to 5% are selected. Depending on this desired Type 1 error rate, the critical value c is calculated. For example, if we select an error rate of 1%, c is calculated thus:

From all the numbers c, with this property, we choose the smallest, in order to minimize the probability of a Type II error, a false negative. For the above example, we select:  .

.

But what if the subject did not guess any cards at all? Having zero correct answers is clearly an oddity too. The probability of guessing incorrectly once is equal to p' = (1 − p) = 3/4. Using the same approach we can calculate that probability of randomly calling all 25 cards wrong is:

This is highly unlikely (less than 1 in a 1000 chance). While the subject can't guess the cards correctly, dismissing H0 in favour of H1 would be an error. In fact, the result would suggest a trait on the subject's part of avoiding calling the correct card. A test of this could be formulated: for a selected 1% error rate the subject would have to answer correctly at least twice, for us to believe that card calling is based purely on guessing.

Example 3 – Radioactive suitcase

As an example, consider determining whether a suitcase contains some radioactive material. Placed under a Geiger counter, it produces 10 counts per minute. The null hypothesis is that no radioactive material is in the suitcase and that all measured counts are due to ambient radioactivity typical of the surrounding air and harmless objects. We can then calculate how likely it is that we would observe 10 counts per minute if the null hypothesis were true. If the null hypothesis predicts (say) on average 9 counts per minute and a standard deviation of 1 count per minute, then we say that the suitcase is compatible with the null hypothesis (this does not guarantee that there is no radioactive material, just that we don't have enough evidence to suggest there is). On the other hand, if the null hypothesis predicts 3 counts per minute and a standard deviation of 1 count per minute, then the suitcase is not compatible with the null hypothesis, and there are likely other factors responsible to produce the measurements.

The test described here is more fully the null-hypothesis statistical significance test. The null hypothesis represents what we would believe by default, before seeing any evidence. Statistical significance is a possible finding of the test, declared when the observed sample is unlikely to have occurred by chance if the null hypothesis were true. The name of the test describes its formulation and its possible outcome. One characteristic of the test is its crisp decision: to reject or not reject the null hypothesis. A calculated value is compared to a threshold, which is determined from the tolerable risk of error.

Example 4 – Lady tasting tea

The following example is summarized from Fisher, and is known as the Lady tasting tea example.[4] Fisher thoroughly explained his method in a proposed experiment to test a Lady's claimed ability to determine the means of tea preparation by taste. The article is less than 10 pages in length and is notable for its simplicity and completeness regarding terminology, calculations and design of the experiment. The example is loosely based on an event in Fisher's life. The Lady proved him wrong.[5]

- The experiment provided the Lady with 8 randomly ordered cups of tea - 4 prepared by first adding milk, 4 prepared by first adding the tea. She was to select the 4 cups prepared by one method.

- This offered the Lady the advantage of judging cups by comparison.

- The Lady was fully informed of the experimental method.

- The null hypothesis was that the Lady had no such ability.

- The test statistic was a simple count of the number of successes in selecting the 4 cups.

- The null hypothesis distribution was computed by the number of permutations. The number of selected permutations equaled the number of unselected permutations.

| Success count | Permutations of selection | Number of permutations |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | oooo | 1 × 1 = 1 |

| 1 | ooox, ooxo, oxoo, xooo | 4 × 4 = 16 |

| 2 | ooxx, oxox, oxxo, xoxo, xxoo, xoox | 6 × 6 = 36 |

| 3 | oxxx, xoxx, xxox, xxxo | 4 × 4 = 16 |

| 4 | xxxx | 1 × 1 = 1 |

| Total | 70 |

- The critical region was the single case of 4 successes of 4 possible based on a conventional probability criterion (< 5%; 1 of 70 ≈ 1.4%).

- Fisher asserted that no alternative hypothesis was (ever) required.

If and only if the Lady properly categorized all 8 cups was Fisher willing to reject the null hypothesis – effectively acknowledging the Lady's ability with > 98% confidence (but without quantifying her ability). Fisher later discussed the benefits of more trials and repeated tests.

The testing process

In the statistical literature, statistical hypothesis testing plays a fundamental role.[6] The usual line of reasoning is as follows:

- We start with a research hypothesis of which the truth is unknown.

- The first step is to state the relevant null and alternative hypotheses. This is important as mis-stating the hypotheses will muddy the rest of the process. Specifically, the null hypothesis allows to attach an attribute: it should be chosen in such a way that it allows us to conclude whether the alternative hypothesis can either be accepted or stays undecided as it was before the test.[7]

- The second step is to consider the statistical assumptions being made about the sample in doing the test; for example, assumptions about the statistical independence or about the form of the distributions of the observations. This is equally important as invalid assumptions will mean that the results of the test are invalid.

- Decide which test is appropriate, and stating the relevant test statistic T.

- Derive the distribution of the test statistic under the null hypothesis from the assumptions. In standard cases this will be a well-known result. For example the test statistics may follow a Student's t distribution or a normal distribution.

- The distribution of the test statistic partitions the possible values of T into those for which the null-hypothesis is rejected, the so called critical region, and those for which it is not.

- Compute from the observations the observed value tobs of the test statistic T.

- Decide to either fail to reject the null hypothesis or reject it in favor of the alternative. The decision rule is to reject the null hypothesis H0 if the observed value tobs is in the critical region, and to accept or "fail to reject" the hypothesis otherwise.

It is important to note the philosophical difference between accepting the null hypothesis and simply failing to reject it. The "fail to reject" terminology highlights the fact that the null hypothesis is assumed to be true from the start of the test; if there is a lack of evidence against it, it simply continues to be assumed true. The phrase "accept the null hypothesis" may suggest it has been proved simply because it has not been disproved, a logical fallacy known as the argument from ignorance. Unless a test with particularly high power is used, the idea of "accepting" the null hypothesis may be dangerous. Nonetheless the terminology is prevalent throughout statistics, where its meaning is well understood.

Alternatively, if the testing procedure forces us to reject the null hypothesis (H-null), we can accept the alternative hypothesis (H-alt) and we conclude that the research hypothesis is supported by the data. This fact expresses that our procedure is based on probabilistic considerations in the sense we accept that using another set could lead us to a different conclusion.

Definition of terms

The following definitions are mainly based on the exposition in the book by Lehmann and Romano:[8]

- Statistical hypothesis

- A statement about the parameters describing a population (not a sample).

- Statistic

- A value calculated from a sample, often to summarize the sample for comparison purposes.

- Simple hypothesis

- Any hypothesis which specifies the population distribution completely.

- Composite hypothesis

- Any hypothesis which does not specify the population distribution completely.

- Null hypothesis

- A simple hypothesis associated with a contradiction to a theory one would like to prove.

- Alternate hypothesis

- A hypothesis (often composite) associated with a theory one would like to prove.

- Statistical test

- A decision function that takes its values in the set of hypotheses.

- Region of acceptance

- The set of values for which we fail to reject the null hypothesis.

- Region of rejection / Critical region

- The set of values of the test statistic for which the null hypothesis is rejected.

- Power of a test (1 − β)

- The test's probability of correctly rejecting the null hypothesis. The complement of the false negative rate, β.

- Size / Significance level of a test (α)

- For simple hypotheses, this is the test's probability of incorrectly rejecting the null hypothesis. The false positive rate. For composite hypotheses this is the upper bound of the probability of rejecting the null hypothesis over all cases covered by the null hypothesis.

- p-value

- The probability, assuming the null hypothesis is true, of observing a result at least as extreme as the test statistic.

- Statistical significance test

- A predecessor to the statistical hypothesis test. An experimental result was said to be statistically significant if a sample was sufficiently inconsistent with the (null) hypothesis. This was variously considered common sense, a pragmatic heuristic for identifying meaningful experimental results, a convention establishing a threshold of statistical evidence or a method for drawing conclusions from data. The statistical hypothesis test added mathematical rigor and philosophical consistency to the concept by making the alternative hypothesis explicit. The term is loosely used to describe the modern version which is now part of statistical hypothesis testing.

- Similar test

- When testing hypotheses concerning a subset of the parameters describing the distribution of the observed random variables, a similar test is one whose distribution, under the null hypothesis, is independent of the nuisance parameters (the ones not being tested).

A statistical hypothesis test compares a test statistic (z or t for examples) to a threshold. The test statistic (the formula found in the table below) is based on optimality. For a fixed level of Type I error rate, use of these statistics minimizes Type II error rates (equivalent to maximizing power). The following terms describe tests in terms of such optimality:

- Most powerful test

- For a given size or significance level, the test with the greatest power.

- Uniformly most powerful test (UMP)

- A test with the greatest power for all values of the parameter being tested.

- Consistent test

- When considering the properties of a test as the sample size grows, a test is said to be consistent if, for a fixed size of test, the power against any fixed alternative approaches 1 in the limit.[9]

- Unbiased test

- For a specific alternative hypothesis, a test is said to be unbiased when the probability of rejecting the null hypothesis is not less than the significance level when the alternative is true and is less than or equal to the significance level when the null hypothesis is true.

- Conservative test

- A test is conservative if, when constructed for a given nominal significance level, the true probability of incorrectly rejecting the null hypothesis is never greater than the nominal level.

- Uniformly most powerful unbiased (UMPU)

- A test which is UMP in the set of all unbiased tests.

Interpretation

The direct interpretation is that if the p-value is less than the required significance level, then we say the null hypothesis is rejected at the given level of significance. Criticism on this interpretation can be found in the corresponding section.

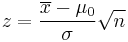

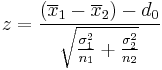

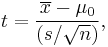

Common test statistics

In the table below, the symbols used are defined at the bottom of the table. Many other tests can be found in other articles.

| Name | Formula | Assumptions or notes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-sample z-test |  |

(Normal population or n > 30) and σ known. (z is the distance from the mean in relation to the standard deviation of the mean). For non-normal distributions it is possible to calculate a minimum proportion of a population that falls within k standard deviations for any k (see: Chebyshev's inequality). |

|||

| Two-sample z-test |  |

Normal population and independent observations and σ1 and σ2 are known | |||

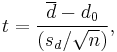

| One-sample t-test |

|

(Normal population or n > 30) and s unknown | |||

| Paired t-test |

|

(Normal population of differences or n > 30) and s unknown | |||

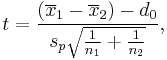

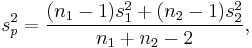

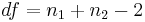

| Two-sample pooled t-test, equal variances* |  |

(Normal populations or n1 + n2 > 40) and independent observations and σ1 = σ2 unknown | |||

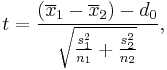

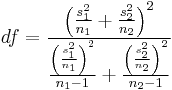

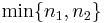

| Two-sample unpooled t-test, unequal variances* |  |

(Normal populations or n1 + n2 > 40) and independent observations and σ1 ≠ σ2 both unknown | |||

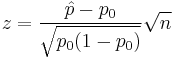

| One-proportion z-test |  |

n .p0 > 10 and n (1 − p0) > 10 and it is a SRS (Simple Random Sample), see notes. | |||

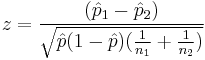

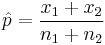

Two-proportion z-test, pooled for  |

|

n1 p1 > 5 and n1(1 − p1) > 5 and n2 p2 > 5 and n2(1 − p2) > 5 and independent observations, see notes. | |||

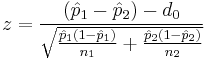

Two-proportion z-test, unpooled for  |

|

n1 p1 > 5 and n1(1 − p1) > 5 and n2 p2 > 5 and n2(1 − p2) > 5 and independent observations, see notes. | |||

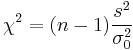

| Chi-squared test for variance |  |

||||

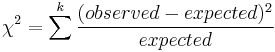

| Chi-squared test for goodness of fit |  |

df = k - 1 - # parameters estimated, and one of these must hold.

• All expected counts are at least 5.[11] • All expected counts are > 1 and no more than 20% of expected counts are less than 5. |

|||

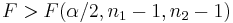

| *Two-sample F test for equality of variances |  |

Arrange so  > >  and reject H0 for and reject H0 for  [12] [12] |

|||

In general, the subscript 0 indicates a value taken from the null hypothesis, H0, which should be used as much as possible in constructing its test statistic. ... Definitions of other symbols:

|

|||||

Origins

Hypothesis testing is largely the product of Ronald Fisher, Jerzy Neyman, Karl Pearson and (son) Egon Pearson. Fisher was an agricultural statistician who emphasized rigorous experimental design and methods to extract a result from few samples assuming Gaussian distributions. Neyman (who teamed with the younger Pearson) emphasized mathematical rigor and methods to obtain more results from many samples and a wider range of distributions. Modern hypothesis testing is an (extended) hybrid of the Fisher vs Neyman/Pearson formulation, methods and terminology developed in the early 20th century.

Importance

Statistical hypothesis testing plays an important role in the whole of statistics and in statistical inference. For example, Lehmann (1992) in a review of the fundamental paper by Neyman and Pearson (1933) says: "Nevertheless, despite their shortcomings, the new paradigm formulated in the 1933 paper, and the many developments carried out within its framework continue to play a central role in both the theory and practice of statistics and can be expected to do so in the foreseeable future".

Significance testing has been the favored statistical tool in some experimental social sciences (over 90% of articles in the Journal of Applied Psychology during the early 1990s). [13] Other fields have favored the estimation of parameters. Editors often consider significance as a criterion for the publication of scientific conclusions based on experiments with statistical results.

Controversy

Since significance tests were first popularized many objections have been voiced by prominent and respected statisticians. The volume of criticism and rebuttal has filled books with language seldom used in the scholarly debate of a dry subject.[14] [15] [16] [17] Much of the criticism was published more than 40 years ago. The fires of controversy have burned hottest in the field of experimental psychology. Nickerson surveyed the issues in the year 2000.[18] He included 300 references and reported 20 criticisms and almost as many recommendations, alternatives and supplements. The following section greatly condenses Nickerson's discussion, omitting many issues.

Selected criticisms

- There are numerous persistent misconceptions regarding the test and its results.

- The test is a flawed application of probability theory.

- While the data can be unlikely given the null hypothesis, the alternative hypothesis can be even more unlikely. (Nobody can be that lucky. vs. Clairvoyance is impossible.)

- The test result is a function of sample size.

- The test result is uninformative.

- Statistical significance does not imply practical significance.

- Statistical testing harms forecasting success[19]

- Using statistical significance as a criterion for publication results in problems collectively known as publication bias.

- Published Type I errors are difficult to correct.

- Published effect sizes are biased upward.

- Meta-studies are biased by the invisibility of tests which failed to reach significance.

- Type II errors (false negatives) are common.

Each criticism has merit, but is subject to discussion.

Misuses and abuses

The characteristics of significance tests can be abused. When the test statistic is close to the chosen significance level, the temptation to carefully treat outliers, to adjust the chosen significance level, to pick a better statistic or to replace a two-tailed test with a one-tailed test can be powerful. If the goal is to produce a significant experimental result:

- Conduct a few tests with a large sample size.

- Rigorously control the experimental design.

- Publish the successful tests; Hide the unsuccessful tests.

- Emphasize the statistical significance of the results if the practical significance is doubtful.

If the goal is to fail to produce a significant effect:

- Conduct a large number of tests with inadequate sample size.

- Minimize experimental design constraints.

- Publish the number of tests conducted that show "no significant result".

Results of the controversy

The controversy has produced several results. The American Psychological Association has strengthened its statistical reporting requirements after review,[20] medical journal publishers have recognized the obligation to publish some results that are not statistically significant to combat publication bias[21] and a journal has been created to publish such results exclusively.[22] Textbooks have added some cautions and increased coverage of the tools necessary to estimate the size of the sample required to produce significant results. Major organizations have not abandoned use of significance tests although they have discussed doing so.

Alternatives to significance testing

The numerous criticisms of significance testing do not lead to a single alternative or even to a unified set of alternatives. As a result, statistical testing impedes communication between the author and the reader.[23] A unifying position of critics is that statistics should not lead to a conclusion or a decision but to a probability or to an estimated value with confidence bounds. The Bayesian statistical philosophy is therefore congenial to critics who believe that an experiment should simply alter probabilities and that conclusions should only be reached on the basis of numerous experiments.

One strong critic of significance testing suggested a list of reporting alternatives:[24] effect sizes for importance, prediction intervals for confidence, replications and extensions for replicability, meta-analyses for generality. None of these suggested alternatives produces a conclusion/decision. Lehmann said that hypothesis testing theory can be presented in terms of conclusions/decisions, probabilities, or confidence intervals. "The distinction between the ... approaches is largely one of reporting and interpretation." [25]

On one "alternative" there is no disagreement: Fisher himself said, [4] "In relation to the test of significance, we may say that a phenomenon is experimentally demonstrable when we know how to conduct an experiment which will rarely fail to give us a statistically significant result." Cohen, an influential critic of significance testing, concurred,[26] "...don't look for a magic alternative to NHST [null hypothesis significance testing] ... It doesn't exist." "...given the problems of statistical induction, we must finally rely, as have the older sciences, on replication." The "alternative" to significance testing is repeated testing. The easiest way to decrease statistical uncertainty is by more data, whether by increased sample size or by repeated tests. Nickerson claimed to have never seen the publication of a literally replicated experiment in psychology.[18]

While Bayesian inference is a possible alternative to significance testing, it requires information that is seldom available in the cases where significance testing is most heavily used.

Future of the controversy

It is unlikely that this controversy will be resolved in the near future. The flaws and unpopularity of significance testing do not eliminate the need for an objective and transparent means of reaching conclusions regarding experiments that produce statistical results. Critics have not unified around an alternative. Other forms of reporting confidence or uncertainty will probably grow in popularity.

Improvements

Jones and Tukey suggested a modest improvement in the original null-hypothesis formulation to formalize handling of one-tail tests.[27] They conclude that, in the "Lady Tasting Tea" example, Fisher ignored the 8-failure case (equally improbable as the 8-success case) in the example test involving tea, which altered the claimed significance by a factor of 2.

See also

- Comparing means test decision tree

- Complete spatial randomness

- Counternull

- Multiple comparisons

- Omnibus test

- Behrens–Fisher problem

- Bootstrapping (statistics)

- Checking if a coin is fair

- Falsifiability

- Fisher's method for combining independent tests of significance

- Look-elsewhere effect

- Modifiable areal unit problem

- Null hypothesis

- P-value

- Representation theory

- Spatial autocorrelation

- Statistical theory

- Statistical significance

- Type I error, Type II error

- Exact test

For a reconstruction and defense of Neyman–Pearson testing, see Mayo and Spanos, (2006), "Severe Testing as a Basic Concept in a Neyman–Pearson Philosophy of Induction," GJPS, 57: 323–57.

References

- ^ R. A. Fisher (1925). Statistical Methods for Research Workers, Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd, 1925, p.43.

- ^ Cramer, Duncan; Dennis Howitt (2004). The Sage Dictionary of Statistics. p. 76. ISBN 076194138X.

- ^ Schervish, M (1996) Theory of Statistics, p. 218. Springer ISBN 0387945466

- ^ a b Fisher, Sir Ronald A. (1956) [1935]. "Mathematics of a Lady Tasting Tea". In James Roy Newman. The World of Mathematics, volume 3 [Design of Experiments]. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 9780486411514. http://books.google.com/?id=oKZwtLQTmNAC&pg=PA1512&dq=%22mathematics+of+a+lady+tasting+tea%22. Originally from Fisher's book Design of Experiments.

- ^ Box, Joan Fisher (1978). R.A. Fisher, The Life of a Scientist. New York: Wiley. p. 134. ISBN 0471093009.

- ^ Lehmann,1970

- ^ Adèr,J.H. (2008). Chapter 12: Modelling. In H.J. Adèr & G.J. Mellenbergh (Eds.) (with contributions by D.J. Hand), Advising on Research Methods: A consultant's companion (pp. 183–209). Huizen, The Netherlands: Johannes van Kessel Publishing

- ^ Lehmann, E.L.; Joseph P. Romano (2005). Testing Statistical Hypotheses (3E ed.). New York: Springer. ISBN 0387988645.

- ^ Cox, D.R.; D.V. Hinkley (1974). Theoretical Statistics. p. 317. ISBN 0412124293.

- ^ a b NIST handbook: Two-Sample t-Test for Equal Means

- ^ Steel, R.G.D, and Torrie, J. H., Principles and Procedures of Statistics with Special Reference to the Biological Sciences., McGraw Hill, 1960, page 350.

- ^ NIST handbook: F-Test for Equality of Two Standard Deviations (Testing standard deviations the same as testing variances)

- ^ Hubbard, R.; Parsa, A. R.; Luthy, M. R. (1997). "The spread of statistical significance testing in psychology: The case of the Journal of Applied Psychology". Theory and Psychology 7: 545–554.

- ^ Harlow, Lisa Lavoie; Stanley A. Mulaik; James H. Steiger, ed (1997). What If There Were No Significance Tests?. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 978-0-8058-2634-0.

- ^ Morrison, Denton; Henkel, Ramon, ed (2006) [1970]. The Significance Test Controversy. ISBN 0-202-30879-0.

- ^ McCloskey, Deirdre N.; Stephen T. Ziliak (2008). The Cult of Statistical Significance: How the Standard Error Costs Us Jobs, Justice, and Lives. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472050079.

- ^ Chow, Siu L. (1997). Statistical Significance: Rationale, Validity and Utility. ISBN 0-7619-5205-5.

- ^ a b Nickerson, Raymond S. (2000). "Null Hypothesis Significance Tests: A Review of an Old and Continuing Controversy". Psychological Methods 5 (2): 241–301.

- ^ J. Scott Armstrong (2007). "Statistical Tests Harm Progress in Forecasting". pp. 321–327. http://marketing.wharton.upenn.edu/documents/research/StatSigIJF361.pdf.

- ^ Wilkinson, Leland (1999). "Statistical Methods in Psychology Journals; Guidelines and Explanations". American Psychologist 54 (8): 594–604.

- ^ ICMJE website: http://www.icmje.org/

- ^ JASNH website: JASNH homepage

- ^ J. Scott Armstrong. [http://marketing.wharton.upenn.edu/documents/research/StatSigReplyR10-2.pdf "Statistical Significance Tests are Unnecessary Even When Properly Done and Properly Interpreted: Reply to Commentaries"]. http://marketing.wharton.upenn.edu/documents/research/StatSigReplyR10-2.pdf.

- ^ Armstrong, J. Scott (2007). "Significance tests harm progress in forecasting". International Journal of Forecasting 23: 321–327. doi:10.1016/j.ijforecast.2007.03.004.

- ^ E. L. Lehmann (1997). "Testing Statistical Hypotheses: The Story of a Book". Statistical Science 12 (1): 48–52.

- ^ Jacob Cohen (December 1994). "The Earth Is Round (p < .05)". American Psychologist 49 (12): 997–1003. This paper lead to the review of statistical practices by the APA. Cohen was a member of the Task Force that did the review.

- ^ Jones LV, Tukey JW (December 2000). "A sensible formulation of the significance test". Psychol Methods 5 (4): 411–4. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.5.4.411. PMID 11194204. http://content.apa.org/journals/met/5/4/411.

Further reading

- Lehmann, E.L.(1970). Testing statistical hypothesis (5th ed.). Ney York: Wiley.

- Lehmann E.L. (1992) "Introduction to Neyman and Pearson (1933) On the Problem of the Most Efficient Tests of Statistical Hypotheses". In: Breakthroughs in Statistics, Volume 1, (Eds Kotz, S., Johnson, N.L.), Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-94037-5 (followed by reprinting of the paper)

- Neyman, J.; Pearson, E.S. (1933). "On the Problem of the Most Efficient Tests of Statistical Hypotheses". Phil. Trans. R. Soc., Series A 231: 289–337. doi:10.1098/rsta.1933.0009.

External links

- Wilson González, Georgina; Karpagam Sankaran (September 10, 1997). "Hypothesis Testing". Environmental Sampling & Monitoring Primer. Virginia Tech. http://www.cee.vt.edu/ewr/environmental/teach/smprimer/hypotest/ht.html.

- Bayesian critique of classical hypothesis testing

- Critique of classical hypothesis testing highlighting long-standing qualms of statisticians

- Dallal GE (2007) The Little Handbook of Statistical Practice (A good tutorial)

- References for arguments for and against hypothesis testing

- Statistical Tests Overview: How to choose the correct statistical test

- An Interactive Online Tool to Encourage Understanding Hypothesis Testing

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

, the

, the  =

=  = sample 1 size

= sample 1 size = sample 2 size

= sample 2 size =

=  = hypothesized

= hypothesized  = population 1 mean

= population 1 mean = population 2 mean

= population 2 mean =

=  =

=  = sum (of k numbers)

= sum (of k numbers) =

=  =

=  = sample 1 standard deviation

= sample 1 standard deviation = sample 2 standard deviation

= sample 2 standard deviation =

=  =

=  = sample mean of differences

= sample mean of differences = hypothesized population mean difference

= hypothesized population mean difference = standard deviation of differences

= standard deviation of differences = x/n = sample

= x/n = sample  = hypothesized population proportion

= hypothesized population proportion = proportion 1

= proportion 1 = proportion 2

= proportion 2 = hypothesized difference in proportion

= hypothesized difference in proportion = minimum of n1 and n2

= minimum of n1 and n2

=

=  =

=